America’s Roadside Evangelist

Prepare to meet

Henry Harrison Mayes

It was in Conway, Arkansas, 2018, where I first saw the unusual cement marker reading, “JESUS IS COMING SOON“. Located next to a highway garage, it was painted purple and featured a uniquely geometric typography that urged drivers to “give account to God.”

Arkansas is known for its high density of churches, so religion is omnipresent and if you drive out of Conway, then there is one church next to the other. So, the message on the side of the road is not really surprising and yet, it looked like a strange plant from another time.

Closer inspection revealed rough cement and weathering, but no indication of its origin.

The instruction on the side of the marker was “Erect in Algeria, 1990–5″. I had no idea what to make of it and dismissed it as typical Southern proselytizing. A strange object between advertising and folk art

Two years later, I was scrolling through a collection of photos of American folk art on Facebook when I noticed the cement marker again—not just one, but a collection with a person next to it and a name.

My online research quickly turned up some results on the man’s history, his work, and photos of markers still existing, mostly in Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Newer photos often came from people like me who graze the southern US for its strange peculiarities and then either write about it on a blog or create YouTube videos or otherwise leave some trace. God bless them, as we would say here in the Ore Mountains. 🙂

It seems to me that in 2022 I will be in the 3rd generation of those obsessed with Mayes work, or rather his obsession, and want to find out everything. Many blog posts about Mayes marker discoveries date back to 2010, and luckily that was a time when people ran their own websites and commented on each other’s posts. Thus, it was possible to understand one or the other sighting in the comments and even to verify it via Google Maps.

So, here is Henry Harrison Mayer’s story and a list of all markers known (to me).

Meet Henry Harrison Mayes From Middleborro, Kentucky

Henry Harrison Mayes was born in Fork Ridge, TN in 1897 to parents Malinda and Lewis “Ed” Mayes.

At age 15, like everyone else in that region, Mayes began working in the coal mines. He wanted to be a preacher, but he didn’t feel educated enough, and he had to support his family.

At the same time, he began to write short verses from the Bible on cardboard and pinned them to telephone poles, he painted them onto rocks and stones or wagons.

From the first interviews in the mid-1940s, it is not yet clear how he came to preach in this special way. In later articles, the origin of his obsession with literally pouring his faith in cement is traced to the following event.

At the age of 19, Mayes had a serious accident in the coal mines. He was pinned against the wall of the mine by a trolley and suffered injuries so severe that his loved ones were told he would not survive the night. He, on the other hand, prayed and promised the God that he would do everything possible to convert as many people to the Christian faith. And obviously God listened and took young Harrison by his word.

Brothers in Spirit

There are many revival stories like this one. Rev. Howard Finster “Man of Visions” of Georgia((wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Finster)), one of America’s most well-known visionary folk artists, worked on his Paradise Garden and created thousands of artworks and painting, after having visions of another world. Ed Stilley((www.stillonthehill.com/edstilleyabout)) from Arkansas, who had a heart attack while working in the fields, had a vision of God healing him if Ed promised to make instruments for children. Or Brother Claude Ely((wikipedia.org/wiki/Ain%27t_No_Grave)), who at the age of 12 on his deathbed wrote the now well-known gospel song “Ain’t No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down” as an answer his prayers.

After making the pact with God, Mayes tried his hand at preaching, but couldn’t really travel with anyone. Even as a gospel singer he didn’t hit the right note, so he did what he did best and painted messages on signs.

“I tried preaching, I tried running revival meetings, and I tried going all over Florida and different places making music. I never could make a go at nothing until I got into this sign work. That was exactly my calling.”

Eliot Wigginton and Margie Bennett, eds.. “Watchman on the Wall,” Foxfire V (NY: Doubleday, 1986), 333

Harrison Mayes became God’s marketing department, putting up over 1,600 wooden or cardboard signs on highways in 25 states by the mid-1940’s.

He did this job on the side throughout his life, and financed everything with donations that he was able to collect here and there. He also earned money as a sign painter for soft drink companies, which on the one hand gave him the opportunity to deepen his craft and on the other hand made him some money for his project.

Outer Space, Earth, Human

Mayes’ drive to spread God’s Word like a soft drink literally knew no bounds. Especially not in quantity. He placed a 10 meter long lettering V(ictory) In God on his Fork Ridge property for aircraft to see. He did the same thing near airports. Travelers, whether by car, plane or train, should prepare to meet their maker (PREPARE TO MEET GOD) – no more and no less.

When Mayes moved with his family to nearby Middlesboro, maybe the only city built in a meteor crater((https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2016/11/town-built-inside-crater.html)), he laid out his house in the shape of a cross, which held the message JESUS SAVES for the people in planes, flying over his home. He called his house “Air Castle” and it’s decorated with the initials PAE on the gable, the meaning of which Mayes kept secret during his lifetime.

The first cement crosses

Eventually, however, the expense of repairing or replacing the weather-exposed signs became too big of a task, so around 1945 Mayes decided to cast cement markers, anticipating that they would still be standing after his death.

The concrete will be standing after I’m dead and gone

The Knoxville News-Sentinel (Knoxville, Tennessee) · 18 Mar 1945, Sun · Page 21

As a design, he chose the classic cross and a heart-shaped marker with a unique geometric typography, which was probably due to the production of the mold.

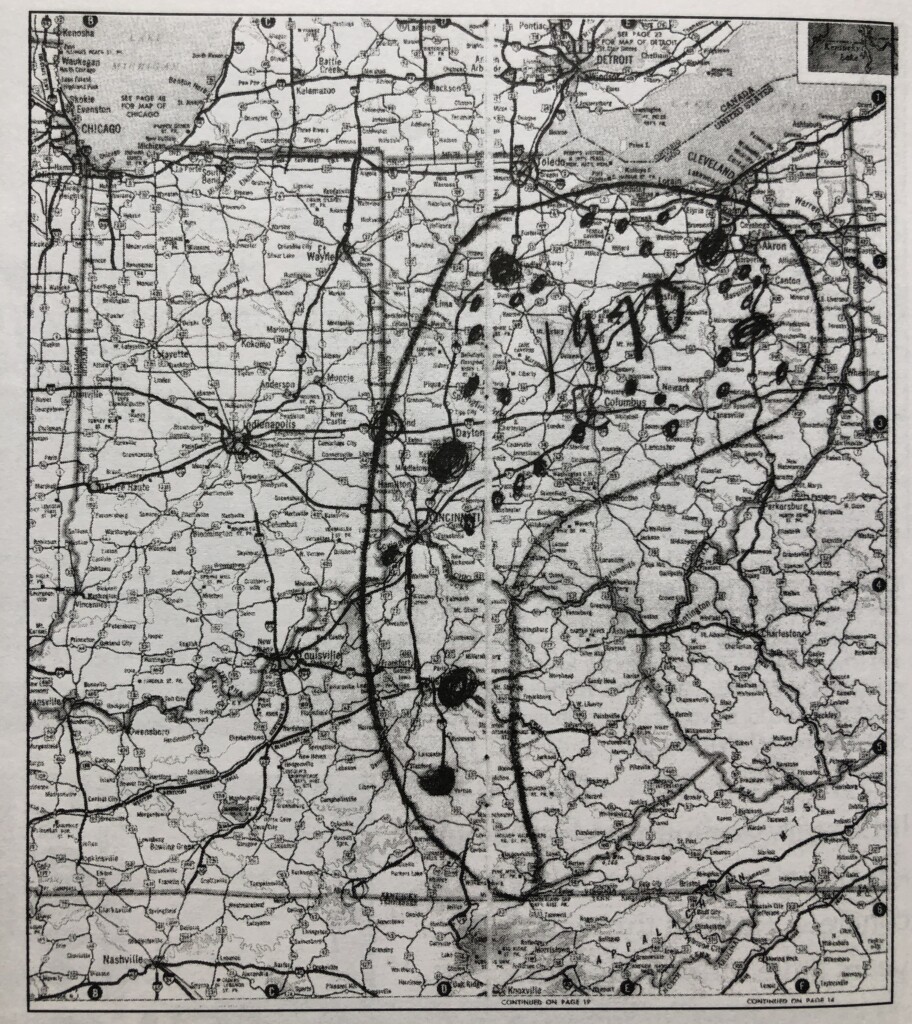

He cast the markers on the lot behind the house and then, during the summer months, he hired acquaintances with a flatbed truck to drive him in all across the US. He set up the markers on public and private land along main highways. Mayes himself did not have a driver’s license and was therefore always dependent on others. Furthermore, they could only deploy 2 of the markers at a time. The erection of the marker itself was often done in 5 minutes after the hole was dug.

Conflicts with the authorities

Of course, Mayes got into trouble with the Highway Code, property owners, and others who weren’t so kind to him. Of course, he broke the law, but Mayes’s belief that “ask for permission doesn’t get you very far” was the way he was able to set up hundreds of markers that still exist today, nearly 40 years after his death. He ignores letters with requests to remove the signs or fees for removing the signs. No one has collected the fees yet and the processors just do as they are told, he bears no grudges.

Every so often, he would also leave a card telling the landowner that he would “rot in hell” if he decided to take down the marker.

Thinking big was also evident in Mayes’ vision of placing markers around the world and even on all nine known planets.

“I want to spread the word of God around the world and in the universe,” he says. “I know there is life out there (on other planets) and they need to be saved too.”

MAYES NAMED each of his five sons after continents, and persuaded her to name his 18 grandchildren and 18 great-grandchildren after planets (Venus, Mercury, Pluto, etc.)—even naming one “Planet X,” for “any new planet of the could be discovered”.

“The way we envision it,” Mayes said, “each of the kids is responsible for putting up signs on the planets they are named after. I think interplanar spaceflight will be pretty common by 2020, so I’m just planning ahead.”

— The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky, Sun, Oct 14, 1973 · Page 77

So many of his markers include the prompt Erect in (Country or Planet) 1990-5, and even his modified bike indicated that Mayes was serious about the planetary excursion.

Mayes was not outspoken about premarital sex or contraception, as some signs indicate. At the same time, he was an early proponent of marriage between black and white Americans, and otherwise not as fanatical as one might think given his missionary work.

I’m not a crank at all

Henry Harrison Mayes

Sign at Museum of Appalachia

God’s Own Sign Painter—Photo by Barney Cowherd

Sign at Museum of Appalachia

In 1975, he had to give up the hard physical work because of his age, but not his urge to send “the good news” to the world. He and his wife focused on placing messages in whiskey bottles and putting them in the water cycle that washed up on stalls here and there around the world.

Message in a bottle has always been a part of the work of Mayes and his wife, Mary Lillie. In this way, they hoped to get their message behind the Iron Curtain. To accomplish this, they sent 4 bottles to the head of the Istanbul post office with a request to put them in the Bosporus, not counting on the current flowing away from the Soviet Union, not in it. However, the package was returned, presumably because no one could read the message in Turkish, written by “linguists” at Lincoln Memorial University.

Whether their plan to have bottles put into the Danube in Vienna worked out is not known, but they toyed with the idea((https://henry-harrison-mayes.tumblr.com/post/676206012148187136)).

In 1988, Henry Harrison Mayes and his wife died. His remaining markers, as well as his bike, remaining signs, and artifacts, were given to the Museum of Appalachia. Too many of his markers have fallen victim to road expansions, accidents, or simply decay over time. In his former sphere of activity, however, there are still traces of “God’s sign painter” to be discovered. His house is still standing albeit without the inscription on the roof, the lighted cross in the mountains above the town is still operational, and a self-published book was published((Book, A Coalminers Simple Message)).

The meaning of the initials PAE came to light 10 years later after opening a time capsule created by Mayes: Planetary Aviation Evangelist was Mayes’ secret and sacred name.

Links

- Prepare to meet Henry Harrison Mayes – A tumblr blog to document my findings

- The Carpetbagger: Harrison Mayes

- The Carpetbagger: Searching for Harrison Mayes on the Rattler

- Strange Carolinas: The Travelogue Of The Offbeat: Search results for Harrison Mayes

- Smith D Ray about Harrison Mayes

- Highway sign evangelist Harrison Mayes – The Courier-Journal

- Harrison Mayes, Signs | SPACES Archives

- The Story Of The Concrete Cross – Part 1 – Only In Arkansas

- Have You Ever Seen A Harrison Mayes Cross? | Blind Pig and The Acorn

- Harrison Mayes Roadside Marker | Fotosammlung

Thanks

This is a Work-In-Progress, and I hope to put as many markers on a virtual map as Harrison Mayes put real markers into the world. I’m sure I’m failing, but who knows, maybe one day there is a way, to put markers on to the google moon map.

Thanks to The Carpetbagger, who created the most extensive collection of markers on the open internet, 10 years ago. His work helped me a lot. Thanks to Chris Hocker of the Strange Carolinas Blog who added the coordinates to some markers, so I didn’t need to spend hours driving around in Google Streetview. Thanks to everyone who published about Mayes on the open internet, so I was able to find so much via Google.

I’m grateful to Eleanor Dickinson for extensively documenting Mayes, introducing his work to the Smithsonian Institute and the Library of Congress, where I had the chance to listen to some of her encounters with Harrison and Lilly Mayes.

Thanks to everyone I didn’t credit (yet) and whose photos I used without asking. I hope you find this a valuable, involuntary contribution. Of course, I will credit you or even remove your photo. Just let me know.